Executive Summary

The year 2026 marks a pivotal moment in the evolution of artificial intelligence governance, as nations, international organizations, and stakeholders converge to establish coherent frameworks for responsible AI innovation. This comprehensive analysis examines the critical summit landscape emerging in 2026, centered around the AI for Good Global Summit in Geneva and the inaugural UN Global Dialogue on AI Governance, while tracking parallel developments in regional regulatory implementation, particularly the EU AI Act’s comprehensive enforcement phase.

Following the unanimous adoption of UN General Assembly Resolution A/79/L.118 in August 2025, which established both the Independent International Scientific Panel on AI and the Global Dialogue on AI Governance, the international community enters 2026 with unprecedented institutional architecture for collaborative AI policymaking. These mechanisms represent the first truly inclusive global approach to AI governance, bringing all 193 UN Member States to the table alongside civil society, industry, and academic stakeholders.

The European Union’s AI Act, which entered into force in August 2024, reaches its critical implementation milestone on August 2, 2026, when comprehensive compliance requirements for high-risk AI systems become fully applicable. This regulatory framework, the world’s first comprehensive legal standard for AI, sets global benchmarks that influence regulatory approaches in the United States, compliance strategies across Europe, and emerging frameworks in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

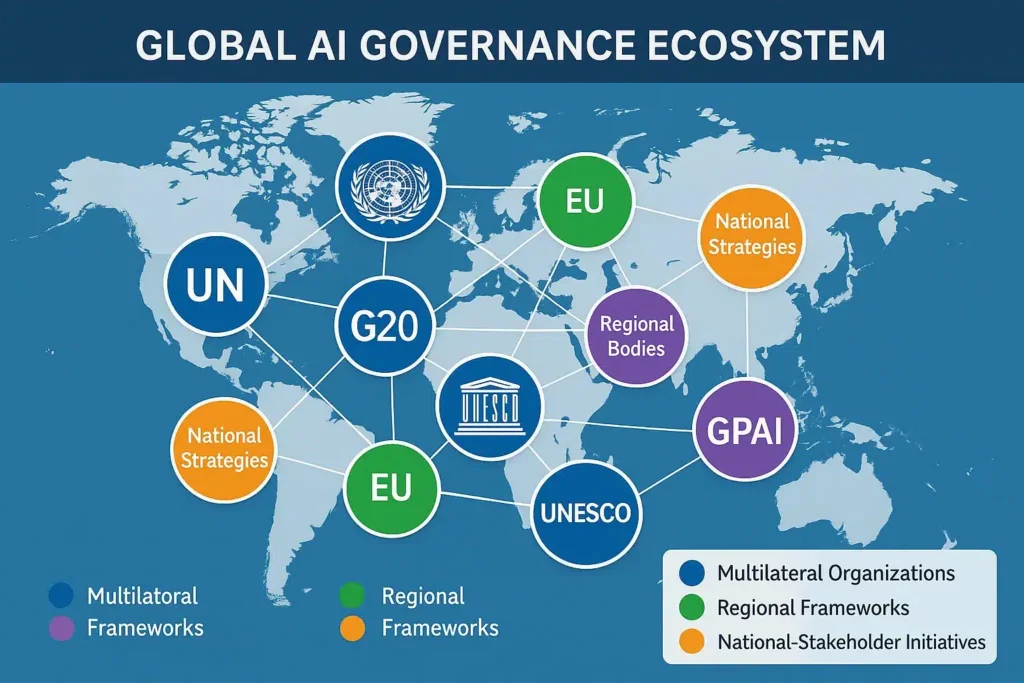

Concurrently, the OECD AI Principles—updated in May 2024 to address general-purpose and generative AI—provide foundational guidance adopted by 47 adherent jurisdictions. The G20’s cooperative framework, maintained across nine years spanning from China’s 2016 presidency through South Africa’s 2025 leadership, demonstrates sustained multilateral commitment to AI governance outside traditional geopolitical rivalries. UNESCO’s 2021 Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, implemented across 194 member states, establishes comprehensive policy action areas addressing data governance, environmental sustainability, gender equality, and societal wellbeing.

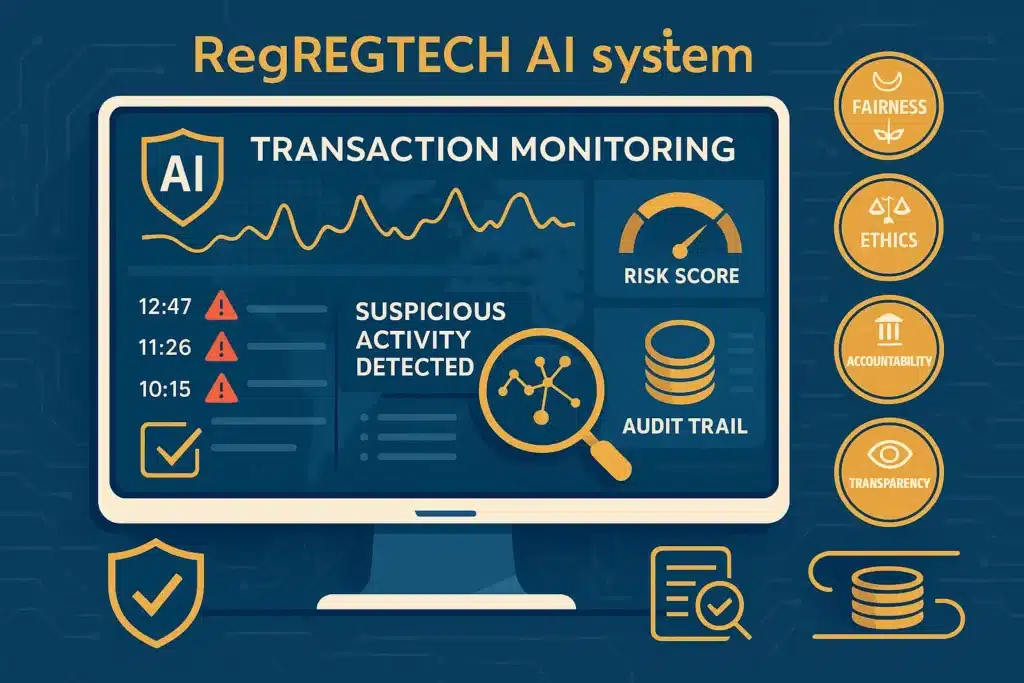

Regional initiatives showcase diverse implementation approaches. Singapore’s Monetary Authority established principles promoting Fairness, Ethics, Accountability, and Transparency (FEAT) in financial services, accompanied by the Veritas framework enabling practical AI system assessment. The Gulf Cooperation Council states, led by Saudi Arabia’s $100 billion Project Transcendence and the UAE’s comprehensive AI Strategy 2031, position themselves as emerging global AI hubs through massive infrastructure investments and talent development programs.

Critical governance challenges dominate the 2026 agenda: managing high-risk AI systems in healthcare, finance, and critical infrastructure; addressing deepfakes and AI-generated misinformation threatening electoral integrity; regulating autonomous systems including military applications; ensuring algorithmic fairness and preventing discriminatory outcomes; protecting privacy while enabling innovation; and bridging the digital divide between AI-capable and AI-vulnerable nations. The emergence of general-purpose AI models with systemic risk potential demands new regulatory approaches balancing innovation incentives with safety imperatives.

This analysis synthesizes developments across multilateral institutions (UN, OECD, G20, UNESCO), regional regulatory regimes (EU, US, UK, Singapore, GCC), sector-specific applications (finance, healthcare, education, transportation), and cross-cutting challenges (cybersecurity, misinformation, bias, accountability). It provides enterprises, policymakers, and stakeholders with actionable intelligence for navigating the complex 2026 governance landscape, emphasizing that effective AI governance requires coordinated action across technical standards, regulatory compliance, ethical frameworks, and international cooperation mechanisms.

The stakes are substantial: properly designed governance frameworks can unlock AI’s transformative potential for sustainable development, scientific advancement, and human flourishing. Fragmented or inadequate governance risks exacerbating inequalities, undermining democratic processes, and enabling harmful applications. The 2026 summit landscape represents a critical window for establishing coherent, interoperable, and human-centric AI governance that serves all of humanity.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence has emerged as the defining technology of the 21st century, reshaping economies, transforming societies, and redefining the boundaries of human capability. As AI systems demonstrate increasingly sophisticated capabilities—from large language models processing natural language to computer vision systems enabling autonomous vehicles—the urgent need for robust governance frameworks intensifies. The year 2026 represents a watershed moment in the global effort to establish responsible, effective, and inclusive AI governance.

The explosive growth of generative AI systems since late 2022 fundamentally altered the AI governance landscape. Technologies that were once confined to research laboratories became accessible to billions of users worldwide within months. This democratization of AI capabilities brought both tremendous opportunities and significant risks, accelerating the imperative for coordinated international action. Governments, international organizations, technology companies, civil society groups, and academic institutions recognized that fragmented, unilateral approaches to AI governance would prove inadequate for technologies that transcend national boundaries and affect all of humanity.

Against this backdrop, 2026 emerges as the year when multiple governance initiatives reach critical implementation phases. The AI for Good Global Summit, organized by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in partnership with over 50 UN agencies and co-convened with the Government of Switzerland, will convene in Geneva alongside the inaugural Global Dialogue on AI Governance. This Global Dialogue, established through UN General Assembly Resolution A/79/325 adopted unanimously in August 2025, provides the first forum where all 193 UN Member States participate equally in shaping international AI cooperation.

The summit landscape extends far beyond a single event in Geneva. It encompasses the European Union’s comprehensive enforcement of the AI Act beginning August 2, 2026; ongoing work by the OECD in refining AI principles and developing internationally comparable indicators; G20 discussions under South Africa’s presidency focusing on AI, data governance, and sustainable development; implementation of UNESCO’s ethical frameworks; and national regulatory developments across dozens of countries at varying stages of AI maturity.

This article provides comprehensive analysis of the 2026 global AI governance summit landscape, examining the institutional architecture being constructed, the substantive policy challenges being addressed, the diverse national and regional approaches being implemented, and the path forward for achieving responsible AI innovation that benefits all humanity. Drawing on authoritative sources including UN documents, OECD publications, EU legislation, academic research, and expert analysis, we trace how the international community is responding to AI’s cybersecurity implications, ethical challenges in healthcare, regulatory requirements in finance, and broader questions of equity, accountability, and human oversight.

Why the Global AI Governance Summit Landscape 2026 Matters

The convergence of multiple governance initiatives in 2026 creates unprecedented opportunities for establishing coherent, interoperable AI frameworks that span jurisdictions and sectors. Understanding why this year holds particular significance requires examining several concurrent developments:

Institutional Maturation

The UN’s AI governance architecture, conceived in 2024 and formally established in 2025, becomes operational in 2026. The Independent International Scientific Panel on AI begins issuing evidence-based assessments synthesizing research on AI opportunities, risks, and impacts. This 40-member panel, comprising leading scientists from diverse geographic and disciplinary backgrounds, serves as an early warning system against threats ranging from disinformation and algorithmic manipulation to autonomous weapons systems. The Global Dialogue provides a platform for exchanging best practices, identifying common approaches, and building consensus on priority areas for international cooperation.

Regulatory Implementation

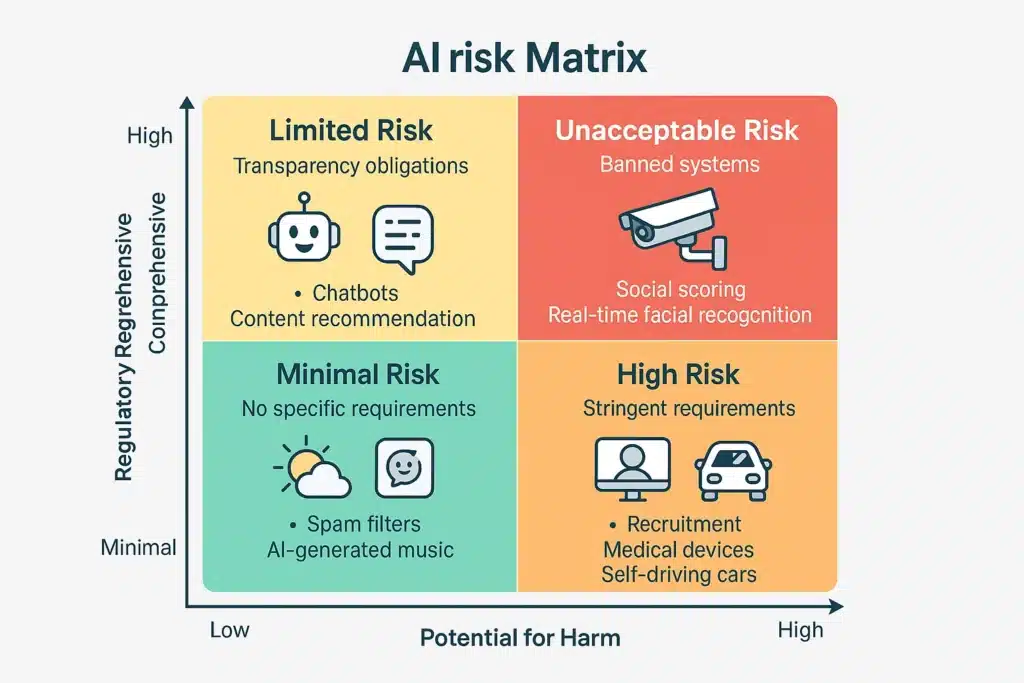

The EU AI Act transitions from legislative text to operational reality. Following the prohibition of unacceptable-risk AI systems (February 2, 2025) and the application of governance requirements for general-purpose AI models (August 2, 2025), the comprehensive framework for high-risk AI systems takes effect August 2, 2026. This milestone affects thousands of organizations globally, as any AI system deployed in the EU market must comply regardless of where development occurred. The Act’s risk-based approach, detailed technical requirements, and substantial penalties (up to €35 million or 7% of global annual turnover) establish de facto global standards influencing regulatory development worldwide.

Technological Inflection Points

AI capabilities continue advancing rapidly. Large language models demonstrate increasingly sophisticated reasoning abilities. Computer vision systems achieve near-human accuracy across diverse recognition tasks. Reinforcement learning enables complex decision-making in dynamic environments. Multimodal systems integrate text, images, audio, and video processing. These advances create both opportunities and governance challenges, as systems become more capable of autonomous operation, generate more realistic synthetic content, and require more complex safety and accountability mechanisms.

Geopolitical Dynamics

AI governance unfolds against significant geopolitical tensions, yet remarkably, multilateral cooperation persists. Analysis of G20 documents spanning 2016-2024 reveals consistent cooperative framing despite global pandemic, ongoing conflicts, and deteriorating great-power relations. The addition of the African Union as a permanent G20 member in 2023 enhances inclusivity. South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency prioritizes equity, sustainability, and meaningful participation of developing countries in shaping AI’s future. This demonstrated commitment to cooperation provides foundation for productive 2026 dialogues.

Economic Stakes

The economic implications of AI governance are substantial. Estimates suggest AI could contribute $15.7 trillion to the global economy by 2030, but realizing this potential requires frameworks that enable innovation while managing risks. The GCC states alone plan investments exceeding $227 billion in AI by 2030. China, the United States, and Europe compete for AI leadership while recognizing interdependence. Developing countries seek to avoid a new digital divide where AI benefits concentrate in wealthy nations. Effective governance can unlock shared prosperity; ineffective governance risks exacerbating global inequalities.

Societal Trust

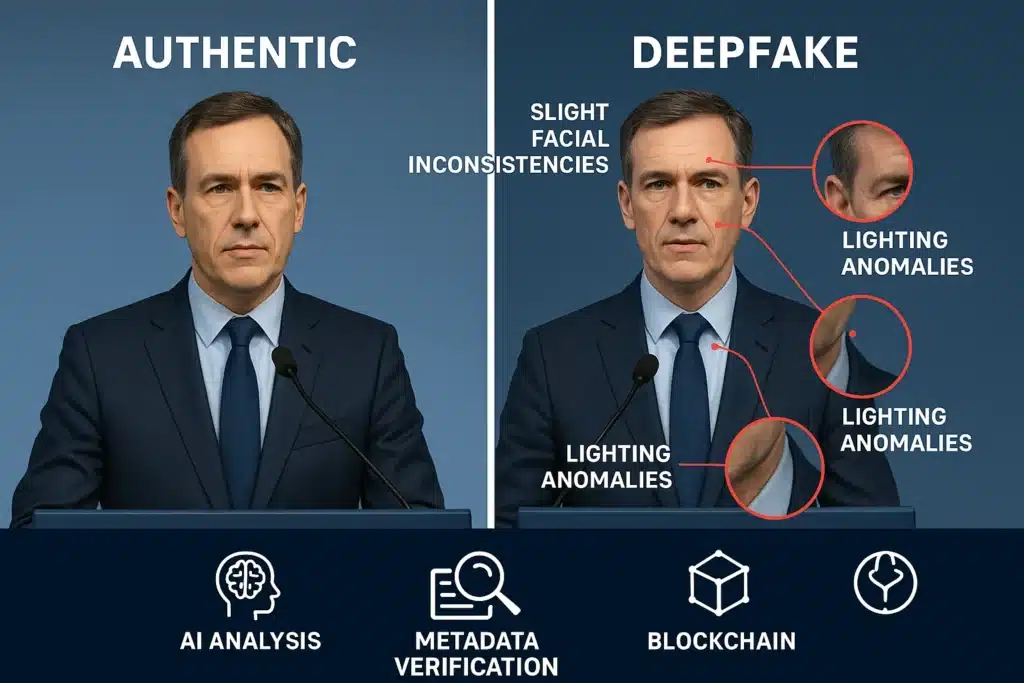

Public confidence in AI systems depends significantly on governance effectiveness. Surveys consistently show majority concern about AI’s societal impacts, from job displacement and privacy erosion to algorithmic discrimination and autonomous weapons. The 2024 elections across 72 countries, affecting 3.7 billion voters, raised concerns about AI-generated deepfakes and misinformation, though impacts proved less catastrophic than feared. Building societal trust requires transparent governance, meaningful accountability, inclusive participation in decision-making, and demonstrated commitment to protecting human rights and democratic values.

The 2026 summit landscape matters because it represents the international community’s response to these converging pressures. The frameworks established, the precedents set, and the cooperation mechanisms activated in 2026 will shape AI’s trajectory for decades. Success requires moving beyond aspirational principles to operational governance that balances innovation with safety, economic growth with equity, and technological advancement with human dignity.

Current State of Global AI Governance

Understanding the 2026 summit landscape requires examining the existing governance architecture that provides its foundation. Multiple international organizations, regional bodies, and national governments have developed frameworks addressing AI’s opportunities and risks. These initiatives vary in scope, bindingness, and implementation stage, yet collectively form an emerging global governance ecosystem.

United Nations Initiatives

The United Nations adopted its first resolution on artificial intelligence on March 21, 2024. Resolution A/78/L.49, titled “Seizing the opportunities of safe, secure and trustworthy artificial intelligence systems for sustainable development,” marked a milestone in multilateral AI governance. Sponsored by the United States and co-sponsored by 123 other member states, the resolution achieved unanimous adoption by all 193 UN members.

This initial resolution emphasized promoting AI systems that are safe, secure, and trustworthy while respecting human rights and fundamental freedoms. It called upon states to refrain from using AI systems in ways inconsistent with international law and human rights obligations. The resolution encouraged developing regulatory and governance approaches, promoting AI literacy, investing in capacity building, and fostering international cooperation on AI for sustainable development.

Building on this foundation, the September 2024 Summit of the Future resulted in adoption of the Pact for the Future, which includes the Global Digital Compact and the Declaration on Future Generations. The Global Digital Compact, based on recommendations from the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence (which issued its report “Governing AI for Humanity” in 2024), committed member states to establish two new AI governance bodies.

Resolution A/RES/79/325, adopted unanimously on August 26, 2025, outlined the terms of reference and modalities for the Independent International Scientific Panel on AI and the Global Dialogue on AI Governance. The Scientific Panel’s mandate includes issuing evidence-based scientific assessments synthesizing and analyzing existing research related to AI’s opportunities, risks, and impacts. The panel produces one annual policy-relevant summary report and provides updates to the General Assembly twice yearly through interactive dialogues with the panel’s Co-Chairs.

The Global Dialogue on AI Governance launched during a high-level multistakeholder meeting on September 25, 2025, during the UN General Assembly’s 80th session. This forum enables governments, industry, civil society, and scientists to share best practices and develop common approaches to AI governance. Crucially, the dialogue ensures meaningful participation of all countries, addressing the reality that 118 countries were not party to any significant international AI governance initiative prior to this UN-led process.

The Global Dialogue will convene in 2026 at the AI for Good Global Summit in Geneva and in 2027 at the multistakeholder forum on science, technology and innovation for the Sustainable Development Goals in New York. Co-Chairs will hold intergovernmental consultations to agree on common understandings on priority areas for international AI governance, feeding into the high-level review of the Global Digital Compact and further discussions.

OECD AI Principles

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development established the first intergovernmental standard on AI with the OECD AI Principles, adopted in 2019 and updated in May 2024. These principles promote innovative, trustworthy AI that respects human rights and democratic values. Currently endorsed by 47 jurisdictions including the European Union, the principles provide a universal blueprint for AI governance.

The 2024 update addressed rapid advances in general-purpose and generative AI, with enhanced focus on safety, privacy, intellectual property rights, and information integrity. The update also refined the OECD’s definition of an AI system to align with latest technological evolutions, providing a foundation upon which governments can legislate and regulate AI. This common definition has been adopted by numerous jurisdictions including the European Union, Council of Europe, Japan, and the United States, facilitating harmonization and interoperability.

The principles comprise five value-based pillars: (1) inclusive growth, sustainable development and well-being; (2) respect for the rule of law, human rights, and democratic values, including addressing misinformation and disinformation amplified by AI while respecting freedom of expression; (3) transparency and explainability; (4) robustness, security and safety, including mechanisms to bolster information integrity; and (5) accountability, with strengthened risk-related requirements including assessment, disclosure, management, monitoring, and notification.

The OECD recommendations for policymakers emphasize: investing in AI research and development; fostering inclusive AI-enabling ecosystems; shaping enabling, interoperable policy environments; building human capacity and preparing for labor market transitions; and pursuing international cooperation for trustworthy AI. The OECD supports implementation through its AI Policy Observatory (OECD.AI), which provides tools and live data on AI policies, incidents, and developments globally.

The OECD’s September 2024 partnership with the United Nations Office of the Tech Envoy and November 2024 collaboration with Saudi Arabia’s SDAIA extending the AI Incidents Monitor to Arabic demonstrate ongoing expansion of the OECD’s global AI governance work. National AI reviews for countries including Germany and Egypt provide detailed assessments of AI readiness and policy frameworks.

G20 Collaborative Framework

The G20’s approach to AI governance demonstrates remarkable continuity and cooperation despite global tensions. Analysis of 71 official G20 documents spanning China’s 2016 presidency through Brazil’s 2024 summit reveals consistent cooperative framing, with language of competition, race, and rivalry notably absent from AI governance contexts. Every presidency has maintained collaborative positioning, treating AI as a shared global project even amid pandemic, conflict, and worsening geopolitical relations.

The G20 adopted AI Principles in 2019 building on the OECD framework. India’s 2023 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration committed to working together to promote international cooperation on international governance for AI, recognizing AI as “fundamentally redefining teaching and learning” and enabling “agile, efficient and evidence-based decision-making.” Brazil’s 2024 presidency highlighted algorithmic bias in hiring and promotions, committing to “harness the benefits of safe, secure, and trustworthy Artificial Intelligence” through governance rather than assuming benefits occur automatically.

South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency established a Task Force on Artificial Intelligence, Data, Governance and Innovation for Sustainable Development, emphasizing optimizing AI’s benefits while mitigating risks. The Task Force affirmed that jurisdictions are entitled to develop, adopt and regulate AI in accordance with international law and applicable legal frameworks, while recognizing the need for meaningful participation of all nations in shaping a fair, inclusive, safe, secure, trustworthy, responsible, ethical, and sustainable global AI landscape.

The G20 welcomed the UN General Assembly resolutions on AI for sustainable development and capacity building, stressing the importance of fostering inclusive multi-stakeholder and multilateral cooperation and global AI governance facilitating meaningful participation of developing countries. Key themes included data governance as imperative for responsible, trustworthy, equitable AI development; adoption of safe AI in public sector to enhance service delivery; strengthening international cooperation on AI scientific research and innovation; and recognizing open science, open innovation, and accessible datasets subject to international obligations and national regulations.

UNESCO Recommendation on AI Ethics

UNESCO produced the first global standard on AI ethics with its Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, adopted unanimously by all 193 Member States on November 23, 2021. This comprehensive framework establishes values consistent with promoting and protecting human rights, human dignity, and environmental sustainability. Unlike some international instruments, the UNESCO Recommendation includes chapters on monitoring, evaluation, and implementation means including readiness assessment and ethics impact assessment to guarantee real change.

The Recommendation’s cornerstone principles emphasize transparency, accountability, and the rule of law online, with strong recognition of the importance of human oversight of AI systems. Extensive policy action areas provide guidance for policymakers to translate core values into action respecting data governance, environment and ecosystems, gender, education and research, and health and social wellbeing, among many spheres.

The framework’s ten core principles include: proportionality and do no harm; safety and security; fairness and non-discrimination; sustainability; right to privacy and data protection; human oversight and determination; transparency and explainability; responsibility and accountability; awareness and literacy; and multi-stakeholder and adaptive governance. These principles guide AI actors in developing trustworthy AI and provide policymakers with recommendations for effective AI policies.

UNESCO’s implementation efforts in 2023-2024 included working groups testing tools, establishing regional roundtables for peer learning, and developing networks including AI Ethics Experts Without Borders and Women 4 Ethical AI. The first Global Forum on Ethics of Artificial Intelligence took place in February 2024 in the Czech Republic, with work underway to launch the global Observatory on Ethics of AI.

In February 2024, UNESCO launched the Global AI Ethics and Governance Observatory at the Global Forum on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence in Kranj, Slovenia. Building upon the 2021 Recommendation, the Observatory provides comprehensive resources for stakeholders confronting ethical dilemmas and societal implications of AI deployment. Tools include the Readiness Assessment Methodology (RAM) enabling governments to evaluate preparedness to implement AI ethically and responsibly, and the AI Ethics and Governance Lab, a collaborative platform where experts worldwide contribute insights, research findings, and best practices.

Key Themes of the 2026 Summit Landscape

The 2026 global AI governance summit landscape coalesces around several overarching themes that cut across institutional boundaries and geographic regions. These themes reflect both the aspirations for AI’s beneficial applications and the urgent need to address emerging risks:

Inclusive Global Participation

A central theme of 2026 is ensuring meaningful participation of all nations in AI governance, particularly countries from the Global South. The UN Global Dialogue represents the first mechanism where all 193 member states participate equally in shaping international AI cooperation. Previous initiatives saw only seven countries—all from the developed world—party to all significant global AI governance frameworks. South Africa’s G20 presidency, following India’s 2023 and Brazil’s 2024 leadership, reinforces the Troika’s focus on addressing inequalities and injustices arising from technologies produced predominantly in the Global North.

Bridging Innovation and Regulation

Balancing innovation incentives with necessary safeguards remains a fundamental governance challenge. The EU AI Act’s risk-based approach exemplifies this balance, proportioning regulatory requirements to AI systems’ risk levels while providing clear compliance pathways. The OECD’s emphasis on enabling, interoperable policy environments reflects recognition that overly restrictive frameworks can stifle beneficial innovation while inadequate regulation enables harms. Regional variations—from Singapore’s principles-based FEAT framework to the GCC’s investment-led strategies—demonstrate diverse approaches to this balance.

Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

Effective AI governance requires participation beyond governments. Technology companies develop and deploy AI systems; civil society organizations advocate for affected communities; academic institutions conduct research on AI’s impacts; standards bodies develop technical specifications. The AI for Good Summit’s engagement of over 50 UN agencies alongside private sector and civil society reflects this multi-stakeholder imperative. However, critics note the UN process’s eight-month negotiation period included only two brief civil society consultations, risking devolving into intergovernmental echo chambers without sustained inclusive engagement.

Interoperability and Harmonization

As AI systems and data flows transcend national boundaries, governance fragmentation creates compliance challenges and risks regulatory arbitrage. The OECD’s common AI system definition, adopted by numerous jurisdictions, enables harmonization. The EU AI Act’s extraterritorial reach influences global standards. However, genuine interoperability requires more than common terminology—it demands compatible risk frameworks, mutual recognition agreements, and coordinated enforcement approaches. The 2026 landscape tests whether multilateral cooperation can achieve meaningful harmonization or whether regulatory divergence will persist.

Addressing Power Asymmetries

AI capabilities and benefits concentrate in a small number of countries and companies. Three countries (United States, China, and to a lesser extent, the European Union members collectively) dominate AI research, development, and deployment. Within countries, a handful of technology companies control foundational models and computing infrastructure. Governance must address these asymmetries—ensuring developing countries access AI benefits, preventing monopolization, enabling meaningful competition, and distributing AI’s economic gains equitably rather than exacerbating existing inequalities.

Trust and Accountability

Public trust in AI systems depends on demonstrable accountability when things go wrong. The EU AI Act’s detailed traceability requirements, risk management obligations, and conformity assessment procedures operationalize accountability. Singapore’s FEAT principles emphasize both internal accountability (clear ownership within organizations) and external accountability (data subjects’ ability to seek recourse and understand decisions). UNESCO’s emphasis on transparency and responsibility reflects global consensus that opacity breeds mistrust while accountability mechanisms foster confidence.

Capacity Building

Many countries lack technical capacity, regulatory expertise, and institutional frameworks for effective AI governance. The Digital Divide risks becoming an AI Divide unless systematic capacity building occurs. G20 discussions emphasize AI for capacity building, with the UAE’s AI Hub for Sustainable Development and similar initiatives co-designed with African stakeholders exemplifying north-south collaboration. UNESCO’s training programs, the OECD’s technical assistance, and bilateral cooperation initiatives collectively work to build governance capacity globally.

Deep-Dive Analysis on Core AI Governance Principles

Placement: Insert at the beginning of the “Deep-Dive Analysis on Core AI Governance Principles” section

Transparency & Explainability

Transparency and explainability constitute foundational requirements for trustworthy AI systems, yet operationalizing these principles remains technically and practically challenging. The EU AI Act mandates that high-risk AI systems provide users with information necessary to understand their operation and use, with detailed documentation requirements covering system purpose, performance limitations, and human oversight measures.

Singapore’s FEAT principles define transparency as providing clear explanations about data usage and decision-making processes without exposing proprietary information. The Monetary Authority of Singapore emphasizes balancing transparency obligations with legitimate concerns about model manipulation or exploitation. For instance, financial institutions deploying AI for fraud detection must carefully consider what information to disclose, as overly detailed explanations could enable malicious actors to circumvent detection systems.

Technical approaches to explainability vary by AI system type. For traditional machine learning models using techniques like decision trees or linear regression, explanations can reference specific features and their contributions to outcomes. For deep neural networks, explanation methods include attention mechanisms highlighting which inputs influenced outputs, saliency maps showing which image regions drove classification decisions, and counterfactual explanations describing how input changes would alter outputs.

However, explanations face inherent limitations. Complex AI systems may operate through emergent behaviors not reducible to simple causal stories. Explanations designed for technical audiences may confuse laypersons, while simplified explanations may mislead by omitting critical nuances. Research shows users often overtrust AI explanations regardless of accuracy, creating risks when explanations are incomplete or incorrect.

The OECD’s updated principles emphasize transparency regarding AI’s purpose, decision-making logic, and significant factors influencing outcomes, while recognizing that transparency must be balanced with protecting intellectual property and preventing gaming of systems. UNESCO’s framework calls for both transparency about AI system design and explainability enabling affected individuals to understand AI-driven decisions impacting them.

AI Accountability & Human Oversight

Establishing clear accountability for AI systems represents a critical governance imperative. The EU AI Act requires high-risk AI system providers to implement quality management systems, maintain technical documentation, enable automatic logging of events, and ensure appropriate human oversight. Deployers must use systems according to instructions, monitor operation, and implement human oversight measures preventing or minimizing risks.

Singapore’s FEAT framework distinguishes between internal accountability (clear ownership within organizations) and external accountability (data subjects’ ability to seek recourse). Internal accountability requires identifying accountable persons, ensuring they have necessary authority and resources, and establishing governance structures for oversight. External accountability demands that affected individuals can challenge decisions, understand how decisions were reached, and obtain meaningful remedies when rights are violated.

Human oversight mechanisms vary based on AI system criticality and risk level. For some applications, oversight may involve human review of all AI outputs before implementation. For others, human-in-the-loop approaches require human approval for critical decisions while allowing automated processing of routine cases. Human-on-the-loop approaches enable humans to monitor operations and intervene when necessary. Human-in-command approaches ensure humans retain ultimate authority even as AI systems operate with significant autonomy.

The challenge of accountability intensifies with AI systems operating across organizational boundaries and jurisdictions. Supply chains may involve model developers, data providers, infrastructure operators, system integrators, and deployers across multiple countries. The EU AI Act attempts to clarify responsibilities by defining specific obligations for providers, importers, distributors, and deployers, but complex value chains create accountability gaps.

Autonomous systems raise particularly acute accountability questions. When AI systems operate independently making consequential decisions—whether autonomous vehicles navigating traffic, algorithmic trading systems executing financial transactions, or predictive policing systems identifying suspects—assigning responsibility for errors or harms becomes legally and ethically complex. Traditional liability frameworks assuming human decision-making may require fundamental revision to address autonomous AI agents.

AI Bias, Fairness, and Inclusion

AI systems can perpetuate, amplify, or even create biases, leading to discriminatory outcomes affecting individuals and groups. Addressing bias requires understanding its sources: biased training data reflecting historical discrimination, proxy variables that correlate with protected attributes, optimization objectives that disadvantage certain groups, and deployment contexts where AI systems interact with biased human decision-makers.

The EU AI Act explicitly prohibits AI systems deploying subliminal techniques manipulating behavior or exploiting vulnerabilities of specific groups including children or persons with disabilities. For high-risk systems, providers must implement bias detection and correction measures throughout development and deployment. Testing must use representative datasets, and ongoing monitoring must identify emerging bias patterns.

Singapore’s FEAT principles require that individuals or groups not be systematically disadvantaged through AI-driven decisions unless decisions can be justified, and that personal attributes used as input factors are justified. Regular reviews must assess whether models behave as designed and whether unintentional bias emerges over time.

UNESCO’s framework calls for AI actors to promote social justice, fairness, and non-discrimination while taking inclusive approaches ensuring AI’s benefits are accessible to all. Research highlighted in UNESCO documents shows machine learning algorithms performing worse for certain demographic groups, such as diabetic retinopathy diagnostics showing significantly lower accuracy for darker-skin individuals compared to lighter-skin individuals.

Fairness itself resists simple definition. Technical fairness criteria include demographic parity (equal outcomes across groups), equal opportunity (equal true positive rates), predictive parity (equal precision), and individual fairness (similar individuals receive similar outcomes). These criteria can conflict mathematically—satisfying one may require violating others. Context determines which fairness criteria matter most, requiring substantive ethical judgments beyond technical optimization.

Intersectionality compounds challenges. Individuals hold multiple identities simultaneously—race, gender, age, disability status, socioeconomic position—and may face unique biases at these intersections not captured by examining each dimension separately. Fairness-aware machine learning must consider these intersections, substantially increasing technical complexity.

Safety & Robustness

AI systems must function reliably under expected conditions while failing safely when encountering unexpected situations. Safety requirements vary dramatically across application domains. Medical AI systems making diagnostic or treatment recommendations must meet stringent safety standards given potential harms to patients. Financial AI systems must prevent market manipulation and ensure regulatory compliance. Autonomous vehicles must navigate safely in complex, dynamic environments.

The EU AI Act requires high-risk AI systems to achieve appropriate levels of accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity. Systems must perform consistently throughout their lifecycle, be resilient to errors or inconsistencies during operation, and resist attempts to alter their use or performance by exploiting vulnerabilities. Technical documentation must include information about system capabilities and limitations, performance metrics under various conditions, and measures implemented to ensure robustness.

The OECD’s updated principles emphasize mechanisms to bolster information integrity while respecting freedom of expression, reflecting concerns about AI-generated misinformation and disinformation. Robustness requirements extend beyond technical reliability to include resilience against adversarial attacks attempting to manipulate AI system behavior.

Adversarial machine learning demonstrates how malicious actors can cause AI systems to fail. Adversarial examples—inputs deliberately crafted to fool AI systems—can cause image classifiers to misidentify objects, speech recognition systems to mishear commands, or autonomous vehicles to misread traffic signs. Defenses against adversarial attacks remain an active research area, with no silver bullet solutions available.

Safety also requires ongoing monitoring after deployment. AI systems may encounter edge cases or distribution shifts where training data doesn’t reflect operational conditions. Performance degradation over time requires detection and remediation. The EU AI Act mandates post-market monitoring systems enabling providers to collect, document, and analyze relevant data on high-risk AI system performance throughout their lifetime.

Data Governance & Privacy

AI systems’ dependence on large datasets creates substantial data governance and privacy challenges. Training effective AI models often requires massive amounts of data, potentially including personal information, proprietary content, or sensitive materials. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) establishes comprehensive requirements for personal data processing, which AI systems must satisfy.

The EU AI Act requires that training, validation, and testing datasets for high-risk AI systems be relevant, representative, free of errors, and complete. Data governance practices must consider biases, data gaps, and appropriate mitigation measures. Special requirements apply to sensitive personal data relating to racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious beliefs, trade union membership, genetic data, biometric data, health data, or data concerning sex life or sexual orientation.

Singapore’s FEAT framework emphasizes data and model accuracy, requiring regular validation to minimize unintentional bias. The Personal Data Protection Commission’s Model AI Governance Framework provides guidance on managing personal data in AI systems, complementing the Monetary Authority’s financial sector-specific requirements.

Data localization requirements in various jurisdictions create compliance complexity. Some countries require that certain data remain within national borders, limiting cross-border AI training and deployment. China’s data security laws restrict cross-border data transfers. India’s proposed data protection legislation includes localization requirements. The GCC states are developing data governance frameworks balancing economic development goals with data sovereignty concerns.

Privacy-enhancing technologies offer partial solutions. Federated learning enables model training across distributed datasets without centralizing data. Differential privacy adds statistical noise ensuring individual data points cannot be re-identified while preserving aggregate patterns. Homomorphic encryption allows computation on encrypted data. However, these techniques often involve accuracy-privacy tradeoffs, and implementing them requires substantial technical expertise.

Intellectual property questions compound data governance challenges. Training AI models on copyrighted content raises questions about fair use, derivative works, and licensing requirements. The EU AI Act’s general-purpose AI model provisions require transparency about copyrighted training data and policies for complying with rights reservations. Ongoing litigation in multiple jurisdictions will shape how copyright law applies to AI training data.

Cybersecurity and AI Misuse

AI systems introduce novel cybersecurity challenges while potentially enabling enhanced security capabilities. AI-powered cybersecurity tools can detect threats, identify vulnerabilities, and respond to attacks more rapidly than traditional approaches. However, AI systems themselves become attack targets, and malicious actors deploy AI for offensive purposes.

The EU AI Act requires high-risk AI systems to be resilient against attempts to alter their use or performance through exploiting system vulnerabilities. Cybersecurity requirements extend throughout the AI system lifecycle, from secure development practices through ongoing security monitoring and patch management. Systems must implement appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure security level appropriate to risks.

AI-specific attack vectors include data poisoning (injecting malicious training data), model stealing (reverse-engineering proprietary models), membership inference (determining whether specific data was in training sets), and adversarial examples (crafting inputs causing misclassification). Traditional cybersecurity approaches may not adequately address these AI-specific threats, requiring new defensive techniques.

Generative AI systems create particular cybersecurity concerns. These systems can generate sophisticated phishing emails, create malware code, automate social engineering attacks, and produce deepfakes for impersonation or manipulation. While AI companies implement restrictions on malicious uses, determined attackers often circumvent safeguards through prompt engineering or by deploying open-source models without restrictions.

The convergence of AI and critical infrastructure protection demands urgent attention. Power grids, water systems, transportation networks, and telecommunications infrastructure increasingly incorporate AI systems for optimization and management. Successful attacks on these systems could cause cascading failures with severe societal consequences. National security implications extend to AI-enabled weapons systems, where cybersecurity vulnerabilities could enable unauthorized access or manipulation.

International cooperation on AI cybersecurity remains limited. No comprehensive international agreement governs offensive AI capabilities or establishes norms for responsible state behavior regarding AI systems. The Budapest Convention on Cybercrime predates modern AI systems. Multilateral discussions on lethal autonomous weapons systems at the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons have not achieved binding agreements.

Cross-Border Regulations

AI systems and data flows transcend national boundaries, creating jurisdictional complexities and regulatory coordination challenges. The EU AI Act applies to AI systems placed on the EU market or where output is used in the EU, regardless of where providers are located—establishing extraterritorial reach similar to GDPR. This approach creates de facto global standards, as organizations serving EU markets must comply with EU requirements.

However, regulatory approaches diverge significantly across jurisdictions. The United States pursues primarily sector-specific regulation rather than comprehensive AI legislation, with agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, Food and Drug Administration, and Department of Transportation applying existing authorities to AI systems. Individual states are enacting their own AI laws, creating potential fragmentation. This federal-versus-state divide complicates compliance for organizations operating nationwide.

China’s approach emphasizes algorithm governance and content control, with regulations focusing on recommendation algorithms, deepfake synthesis, and content moderation. The Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) establishes data protection requirements, while the Data Security Law creates data classification and protection frameworks. Algorithmic recommendation regulations require transparency about recommendation logic and enable user opt-out from algorithmic curation.

The United Kingdom, no longer bound by EU law following Brexit, is developing its own approach emphasizing pro-innovation regulation. The UK government proposes empowering existing regulators to apply AI principles within their domains rather than creating omnibus AI legislation. This contrasts with the EU’s comprehensive, cross-sectoral framework, potentially creating regulatory divergence between the UK and EU despite geographic proximity and economic integration.

Emerging economies face particular challenges. Many countries lack regulatory capacity, technical expertise, and institutional frameworks for effective AI governance. The risk exists that global governance regimes dominated by wealthy countries could impose requirements that developing countries cannot meet, creating barriers to participation in the AI economy. The UN Global Dialogue aims to ensure meaningful developing country participation, but translating participation into influence requires sustained effort.

Data transfer mechanisms create cross-border friction. GDPR adequacy decisions determine which countries provide adequate data protection for EU data transfers. The EU-US Data Privacy Framework, adopted following the invalidation of earlier Safe Harbor and Privacy Shield arrangements, attempts to enable transatlantic data flows. However, surveillance concerns persist, and future legal challenges may invalidate current arrangements. Other jurisdictions negotiate bilateral and multilateral data transfer agreements, creating a complex patchwork.

The OECD AI Principles aim to facilitate interoperability by providing common definitions and frameworks. The 2024 updates enhancing global consistency demonstrate progress. However, achieving genuine interoperability requires more than shared terminology—it demands compatible risk assessment methodologies, mutual recognition of conformity assessments, coordinated enforcement approaches, and mechanisms for resolving cross-border disputes.

High-Risk AI Systems

The EU AI Act’s risk-based approach classifies AI systems according to potential for harm, with heightened requirements for high-risk systems. Annex III lists high-risk AI applications including biometric identification and categorization, critical infrastructure management, education and vocational training, employment and worker management, access to essential private and public services, law enforcement, migration and border control management, and administration of justice and democratic processes.

High-risk classification triggers comprehensive obligations. Providers must establish quality management systems ensuring compliance throughout system lifecycle. Risk management systems must identify and analyze foreseeable risks, estimate risk likelihood and magnitude, evaluate residual risks, and implement appropriate mitigation measures. Technical documentation must provide complete system descriptions, design specifications, performance metrics, and instructions for use.

Data governance requirements mandate that training, validation, and testing datasets are relevant, representative, free of errors, and complete, with appropriate bias mitigation measures. Human oversight provisions require measures enabling persons to whom high-risk AI systems are assigned to understand system capacities and limitations, remain aware of possible automation bias, correctly interpret outputs, and decide not to use the system or override outputs when appropriate.

Conformity assessment procedures verify compliance before systems enter the market. For certain high-risk AI systems, particularly those involving biometrics, third-party conformity assessment by notified bodies is required. For other systems, providers may conduct internal conformity assessments, though they remain liable for accuracy and completeness. CE marking indicates conformity, similar to other regulated products in the EU market.

Post-market surveillance obligations require ongoing monitoring after deployment. Providers must implement systems to proactively collect, document, and analyze relevant data on high-risk AI system performance. Serious incidents must be reported to authorities. When systems fail to comply with requirements or present risks, providers must take immediate corrective action or withdraw systems from the market.

Member States must designate market surveillance authorities responsible for enforcement. These authorities conduct inspections, request information, require providers to modify or withdraw non-compliant systems, and impose penalties for violations. Penalties can reach €35 million or 7% of total worldwide annual turnover for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher—substantial deterrents intended to ensure compliance.

Autonomous Systems & Military AI

Autonomous systems operating without continuous human control raise profound governance challenges. The spectrum extends from supervised autonomy (humans approve all actions) through increasing levels of autonomy to fully autonomous systems making consequential decisions independently. Military applications—lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS)—generate particular ethical and legal concerns.

The United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons has hosted discussions on LAWS since 2014, but states have not reached consensus on binding restrictions. Some countries advocate for prohibitions on autonomous weapons lacking meaningful human control. Others argue existing international humanitarian law adequately regulates autonomous weapons. Technical complexity, definitional disputes, and strategic considerations complicate negotiations.

International humanitarian law requires that weapons systems distinguish between combatants and civilians, be proportionate to military objectives, and enable commanders to accept responsibility for attacks. Whether autonomous systems can satisfy these requirements remains contested. Opponents argue algorithms cannot replicate human judgment required for complex proportionality assessments and that removing humans from lethal force decisions violates human dignity. Proponents contend autonomous systems might outperform humans in precision, potentially reducing civilian casualties.

The UN General Assembly adopted resolution regarding AI in the military domain and its implications for international peace and security on December 24, 2024. The resolution highlights the need for responsible and human-centered use of AI in military contexts, though it does not establish binding restrictions on autonomous weapons. Discussions continue at the Group of Governmental Experts on Emerging Technologies in the Area of Lethal Autonomous Weapons Systems.

Civilian autonomous systems—self-driving vehicles, autonomous drones for delivery or inspection, robotic caregivers—raise related concerns. These systems may cause harm through errors or malfunctions. Liability frameworks must clarify who bears responsibility: the manufacturer, the operator, the algorithm designer, or the autonomous system itself. Proposals for strict liability (manufacturers liable regardless of fault) compete with negligence-based approaches (liability only when reasonable care was not exercised).

Deepfakes, Misinformation & Election Protection

Generative AI systems’ ability to create realistic fake audio, images, and videos—deepfakes—enables novel forms of manipulation, fraud, and election interference. The 2024 election cycle, affecting 3.7 billion voters across 72 countries, raised acute concerns about AI-generated misinformation overwhelming democratic processes. However, actual impacts proved less catastrophic than feared, offering lessons for governance approaches.

Analysis of 2024 elections reveals less than 1% of all fact-checked misinformation during election cycles was AI content, according to Meta. Despite elections across India, the United States, the European Union, and dozens of other countries, major AI-driven disruptions did not materialize. The dreaded “death of truth” has not occurred—at least not due to AI.

Several factors explain this outcome. Detection technologies improved, enabling platforms to identify and remove deepfakes. Government officials conducted tabletop exercises preparing for deepfake scenarios. States enacted laws requiring disclaimers on AI-generated political content or prohibiting deepfakes in certain contexts. Most importantly, voters’ views are fairly entrenched, with research suggesting misinformation has limited persuasive impact when people already hold firm opinions.

However, absence of major 2024 election disruptions does not eliminate deepfake risks. Harassment through non-consensual intimate imagery remains prevalent. Social engineering attacks using voice-cloning and deepfake video enable sophisticated fraud—a Hong Kong finance worker was tricked into paying $25 million based on a deepfake Zoom meeting impersonating company executives. Deepfakes can attack authentication systems relying on voice or facial recognition.

Regulatory responses vary across jurisdictions. The EU AI Act prohibits placing on the market, putting into service, or using AI systems that deploy subliminal techniques manipulating behavior or exploit vulnerabilities to materially distort behavior in ways causing harm. For permitted deepfakes, disclosure requirements mandate clear labeling when content resembles existing persons, objects, or events.

US approaches primarily occur at the state level. Over 100 bills in 40 state legislatures were introduced or passed in 2024 addressing AI-generated deepfakes in elections. Some laws require disclaimers for AI-generated political content. Others impose criminal penalties for malicious deepfakes. Florida legislation awaiting signature would impose up to one year incarceration for election-related deepfakes. However, First Amendment considerations constrain regulation, particularly for satire or parody.

Technical solutions include content authentication systems embedding cryptographic signatures in media at creation, enabling verification of provenance. The Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) develops technical standards for content credentials. Major technology companies including Adobe, Microsoft, and Meta support C2PA standards. However, adoption remains incomplete, and determined actors can strip metadata or create content outside authenticated systems.

Social solutions emphasize media literacy, teaching people to critically evaluate content before sharing, verify information through multiple sources, and understand tell-tale signs of synthetic media. However, as generation quality improves, detection becomes increasingly difficult even for experts. The balance between technical solutions, regulatory approaches, and social resilience will determine societies’ vulnerability to synthetic media manipulation.

Sector-Specific Impacts

Finance (RegTech, Trading AI, AML Automation)

AI in financial services encompasses algorithmic trading, credit scoring, fraud detection, anti-money laundering (AML), regulatory compliance (RegTech), and customer service. Singapore’s Monetary Authority leads sector-specific governance through its FEAT principles promoting Fairness, Ethics, Accountability, and Transparency in AI and Data Analytics (AIDA) usage.

The FEAT framework requires financial institutions to ensure AI-driven decisions are justifiable and accurate, with governance frameworks assessing appropriateness of data attributes used. Regular reviews must validate models for accuracy and minimize unintentional bias. Ethical standards must reflect firms’ overall ethical guidelines. Internal accountability requires clear ownership, while external accountability ensures customers can seek recourse and understand decisions.

The Veritas initiative, led by MAS with 31 industry players, developed assessment methodologies enabling financial institutions to evaluate AIDA solutions against FEAT principles. Veritas Toolkit version 2.0, released as open-source, provides practical guidance for responsible AI use. Project MindForge addresses generative AI risks in finance, developing frameworks for responsible use given efficiency benefits balanced against risks including sophisticated cybercrime, copyright infringement, data risks, and biases.

RegTech applications use AI to automate regulatory compliance, monitoring transactions for suspicious patterns, assessing risks, and generating required reports. Machine learning models can identify potential money laundering more effectively than rule-based systems, adapting to evolving criminal tactics. However, explainability challenges arise—regulators may demand understanding of why transactions were flagged, which opaque neural networks struggle to provide.

Algorithmic trading systems execute trades at speeds impossible for humans, analyzing market data and identifying opportunities. Flash crashes—rapid, deep market declines caused by algorithmic trading—demonstrate risks. The 2010 Flash Crash saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average drop nearly 1,000 points in minutes before recovering. Circuit breakers and other safeguards have since been implemented, but ongoing vigilance is required as algorithms grow more sophisticated.

Credit scoring illustrates bias concerns. Traditional credit scoring incorporated factors correlating with protected characteristics. AI-based scoring can exacerbate this if training data reflects historical discrimination or if proxy variables (like zip codes correlating with race) are used. Fair lending laws prohibit discrimination, but detecting algorithmic discrimination requires sophisticated analysis. The FEAT framework’s fairness requirements aim to prevent systematically disadvantaging individuals without justification.

Healthcare (Diagnostics, Ethics, Safety)

AI in healthcare includes medical imaging analysis, drug discovery, treatment recommendation, administrative automation, and predictive analytics. The potential benefits are substantial—AI can analyze medical images with accuracy matching or exceeding human radiologists, predict patient deterioration enabling earlier intervention, and identify promising drug candidates accelerating development.

However, healthcare AI raises acute ethical concerns. Medical errors can cause severe harm or death, demanding extremely high reliability standards. Algorithmic bias can lead to disparate health outcomes—research shows some diagnostic AI systems perform worse for certain demographic groups, as UNESCO documentation highlights with diabetic retinopathy diagnostics showing significantly lower accuracy for darker-skin individuals.

The EU AI Act classifies AI systems intended for diagnosis or treatment as high-risk, triggering comprehensive requirements. Systems must undergo rigorous clinical validation before deployment. Ongoing monitoring must detect performance degradation. Clear human oversight protocols ensure medical professionals retain final decision authority. Patients must receive information about AI involvement in their care and maintain rights to human review of AI-driven medical decisions.

Data privacy assumes particular importance in healthcare. Medical records contain highly sensitive personal information protected by regulations like HIPAA in the United States and GDPR in Europe. Training AI models on patient data requires careful de-identification, consent management, and security measures. Federated learning approaches enable model training across multiple healthcare institutions without centralizing patient data, but technical complexity limits adoption.

Singapore developed Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare Guidelines through collaboration between the Ministry of Health, Health Sciences Authority, and Integrated Health Information Systems. These guidelines complement medical device regulations, establishing good practices for AI developers. Emphasis is placed on clinical validation, ongoing monitoring, and ensuring AI systems support rather than replace clinical judgment.

The balance between innovation and safety remains delicate. Overly restrictive requirements could delay beneficial technologies, causing preventable suffering. Insufficient requirements risk deploying unsafe systems. Risk-proportionate regulation—more stringent requirements for higher-risk applications—attempts to strike appropriate balance. Ongoing dialogue among clinicians, patients, regulators, and developers will shape healthcare AI governance evolution.

Education

AI in education encompasses personalized learning systems adapting to individual student needs, automated grading reducing teacher workload, proctoring systems monitoring exam integrity, predictive analytics identifying at-risk students, and administrative automation streamlining operations. UNESCO’s work addresses AI in education specifically, recognizing both transformative potential and significant risks.

Personalized learning systems can provide tailored instruction matching students’ learning pace, preferred styles, and knowledge gaps—benefits particularly valuable in resource-constrained environments where teacher-to-student ratios limit individual attention. However, concerns arise about surveillance, privacy invasion through extensive data collection on children, and algorithmic bias potentially reinforcing educational inequalities.

The EU AI Act classifies AI systems used for determining access to educational institutions or assigning students to specific educational institutions as high-risk. Systems evaluating student learning outcomes—unless only detecting violations of exam rules—are also high-risk. These classifications trigger comprehensive compliance requirements including bias assessment, human oversight, and transparency obligations.

Proctoring systems using facial recognition and behavior monitoring raise particular concerns. These systems may falsely flag legitimate behaviors as cheating, disproportionately impacting students with disabilities or neurodiverse students whose behavior patterns may differ. Privacy advocates question whether extensive surveillance is appropriate in educational contexts even if technically effective at detecting cheating.

UNESCO’s recommendation emphasizes that AI in education should enhance rather than replace human teachers. Education remains fundamentally social, requiring human interaction, emotional support, and role modeling that AI cannot provide. Teacher professional development must prepare educators to work effectively with AI tools while maintaining centrality of human pedagogical relationships.

The digital divide in education requires urgent attention. Students without reliable internet access, appropriate devices, or digital literacy cannot benefit from AI-enhanced education. The risk exists that AI exacerbates educational inequalities, with wealthy students accessing sophisticated personalized learning while disadvantaged students fall further behind. Equitable AI deployment requires addressing infrastructure gaps, ensuring universal access, and supporting teachers in under-resourced environments.

Transportation / Autonomous Vehicles

Autonomous vehicles represent one of AI’s most visible and transformative applications. Self-driving cars promise reduced accidents (human error causes approximately 90% of crashes), improved mobility for elderly and disabled individuals, reduced traffic congestion, and transformed urban planning. However, technical challenges, safety concerns, liability questions, and ethical dilemmas complicate deployment.

Levels of driving automation range from Level 0 (no automation) through Level 5 (full automation under all conditions). Most commercially available systems operate at Level 2 or 3, providing driver assistance but requiring human readiness to intervene. Achieving higher automation levels requires solving extraordinarily difficult technical problems including perception in adverse weather, predicting pedestrian behavior, navigating complex urban environments, and handling edge cases that occur rarely but consequentially.

The EU AI Act classifies AI systems intended for operation of autonomous vehicles as high-risk. Vehicle manufacturers must ensure compliance with comprehensive safety requirements, maintain detailed technical documentation, and implement ongoing monitoring. Type-approval procedures under existing automotive regulations integrate AI-specific requirements. Extended transition periods (until August 2, 2027) acknowledge the complexity of bringing existing deployed systems into compliance.

Liability frameworks remain unsettled. When autonomous vehicles cause accidents, determining responsibility among vehicle manufacturers, software developers, component suppliers, vehicle owners, and vehicle occupants creates legal complexity. Some jurisdictions propose strict liability for manufacturers. Others favor negligence-based approaches. Insurance systems must adapt to scenarios where vehicles operate without human drivers.

The famous “trolley problem” takes concrete form with autonomous vehicles. When accidents are unavoidable, how should vehicles prioritize protecting passengers versus pedestrians? Should vehicles swerve to avoid hitting children even if endangering elderly pedestrians? Who decides these ethical tradeoffs, and should they vary across cultures? Research shows public preferences are inconsistent—people want vehicles that protect passengers when they’re riding but protect pedestrians when they’re walking.

Beyond personal vehicles, AI transforms freight transportation, aviation, maritime navigation, and public transit. Autonomous trucks could address driver shortages and reduce logistics costs but might displace millions of professional drivers. Drones for package delivery raise airspace management and privacy concerns. Each domain requires tailored governance balancing innovation benefits against safety imperatives and social impacts.

Public Safety & Smart Cities

AI applications in public safety include predictive policing (forecasting crime locations or identifying high-risk individuals), facial recognition for suspect identification, gunshot detection systems, crowd monitoring, and emergency response optimization. Smart cities integrate these technologies with traffic management, utility optimization, and public service delivery. Benefits include improved public safety and operational efficiency, but risks encompass surveillance, discrimination, and erosion of civil liberties.

Predictive policing uses historical crime data and machine learning to forecast future crime locations or identify individuals likely to offend. Proponents argue this enables more effective resource allocation. Critics contend these systems perpetuate bias—if police historically over-policed certain communities, algorithms trained on this data will direct even more policing to those communities, creating self-fulfilling prophecies and feedback loops reinforcing discrimination.

The EU AI Act explicitly prohibits certain AI uses in public safety contexts. AI systems for social scoring by public authorities—evaluating or classifying people based on behavior, socio-economic status, or personal characteristics—are banned as posing unacceptable risk. Real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces is prohibited with limited exceptions for specific law enforcement purposes subject to strict conditions and safeguards.

Facial recognition accuracy varies significantly across demographic groups. Research shows higher error rates for women, darker-skinned individuals, and elderly people compared to white males. Using such systems for law enforcement could lead to wrongful arrests, as has occurred in multiple documented cases. Some jurisdictions have banned police use of facial recognition; others permit it with restrictions; debates continue about appropriate governance.

Smart city initiatives in the GCC states demonstrate ambitious AI integration. Saudi Arabia’s National Platform Sawaher utilizes AI analyzing streams from over 15,000 cameras for real-time insights and alerts. The UAE’s smart city projects integrate AI across transportation, utilities, government services, and public safety. These implementations offer efficiencies but require careful privacy safeguards and transparency about surveillance capabilities.

Balance between public safety and civil liberties remains contested. Security officials emphasize crime prevention and rapid emergency response. Civil liberties advocates warn about surveillance states, chilling effects on free expression and assembly, and potential for authoritarian misuse. Democratic governance requires robust oversight, clear legal authority, transparency about capabilities and usage, and accountability mechanisms when systems are misused or cause harm.

Media & Creative Industries

Generative AI transforms media and creative industries through automated content creation, personalized news curation, synthetic media production, and creative assistance tools. Journalists use AI for data analysis, automated report generation, and fact-checking. Film and television productions employ AI for visual effects, script analysis, and production optimization. Music industry uses AI for composition, mixing, and recommendation systems.

Benefits include increased productivity, reduced costs, and enhanced creativity as AI handles routine tasks enabling humans to focus on higher-value creative work. AI can analyze vast datasets identifying trends and insights impossible for humans to process manually. Personalized content delivery helps audiences discover relevant material amid information abundance.

However, concerns abound. AI-generated content may displace human creators—writers, artists, musicians—threatening livelihoods in creative industries. Quality concerns arise as AI-generated “content farms” produce low-quality material optimized for search algorithms rather than human readers. Misinformation risks intensify as AI generates plausible-sounding false content at scale. Intellectual property disputes emerge over AI training on copyrighted works and ownership of AI-generated outputs.

The EU AI Act’s general-purpose AI model provisions address creative industries. Providers of GPAI models must prepare technical documentation, provide information to downstream providers, implement copyright compliance policies, and publish summaries of training data. Models with systemic risk require additional safeguards including model evaluation, adversarial testing, tracking serious incidents, and ensuring cybersecurity protections.

Copyright debates intensify. Multiple lawsuits allege AI companies violated copyright by training on protected works without authorization or compensation. Companies argue training constitutes fair use or that copyright doesn’t extend to learning from works. Courts will determine whether existing copyright law adequately addresses AI or whether new frameworks are needed. The EU AI Act requires transparency about copyrighted training content and policies respecting rights reservations.

Media literacy becomes crucial as synthetic content proliferates. Audiences must develop skills to critically evaluate content, verify sources, and recognize AI-generated material. Media organizations implementing AI should maintain transparency about usage, preserve editorial judgment, and ensure accuracy. Industry standards, professional codes of conduct, and audience education collectively shape responsible AI use in media.

Enterprise AI Adoption

Enterprises across sectors adopt AI for customer service automation, supply chain optimization, predictive maintenance, human resources management, and business intelligence. McKinsey surveys show organizations piloting generative AI applications, though many struggle achieving measurable value due to talent shortages, data governance challenges, and organizational barriers.

The GCC region demonstrates particularly high enterprise AI adoption. By late 2024, 75% of GCC companies had implemented generative AI in at least one area versus 65% globally. However, only 11% realized measurable value, with talent shortages and data governance frictions identified as main blockers. One in four GCC companies plans to invest over $25 million in AI in 2025, and over 70% of executives now rank AI among top three strategic priorities.

The “10-20-70” framework for AI transformation—10% success from algorithms, 20% from technology and data, 70% from people, processes, and organizational design—reflects understanding that AI transformation is fundamentally about change management. Technical excellence is necessary but insufficient without appropriate organizational structures, skill development, and cultural adaptation.

Small and medium enterprises face particular challenges. Limited resources, insufficient technical expertise, and risk aversion can inhibit AI adoption despite potential benefits. Governments recognize this challenge—Saudi Arabia’s SDAIA launched “AI for SMEs” initiative in 2024 providing training and subsidies. The UAE runs accelerators helping SMEs implement AI through programs like Dubai’s SME agency and Abu Dhabi’s Hub71. Success stories are emerging: a Kuwaiti retail SME using AI inventory management cut stock costs; a Bahraini fintech SME uses AI for loan underwriting.

Ethics and governance in enterprise AI requires attention beyond regulatory compliance. Organizations should establish AI ethics boards or committees providing oversight. Impact assessments should identify potential harms before deployment. Diverse development teams help identify blind spots and biases. Ongoing monitoring detects emerging problems. Transparency with customers and employees about AI usage builds trust. These practices, while not always legally mandated, represent responsible corporate behavior.

Country & Region Analysis

United States

The United States approaches AI governance through sector-specific regulation by federal agencies and state-level legislation, contrasting with the EU’s comprehensive framework. The October 2023 Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of AI established federal coordination, but comprehensive AI legislation has not passed Congress.

Federal agencies apply existing authorities to AI. The Federal Trade Commission addresses unfair and deceptive practices, investigating companies for AI-related consumer protection violations. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission ensures AI hiring systems don’t discriminate. The Food and Drug Administration regulates AI medical devices. The Department of Transportation oversees autonomous vehicles. This approach leverages existing expertise but creates fragmentation.

State-level AI regulation accelerates. By 2024, over 100 bills in 40 state legislatures addressed AI governance. Colorado passed comprehensive AI regulation, California enacted multiple AI-related bills, and numerous states address specific issues like deepfakes in elections, AI in hiring, or automated decision systems. This creates compliance complexity for organizations operating nationwide.

The US AI Safety Institute Consortium, established within NIST in February 2024 with over 200 stakeholders, develops guidelines and standards for AI safety, security, and trustworthiness. While voluntary rather than regulatory, these standards influence industry practice and potentially inform future regulation.

US leadership in AI development—home to most leading AI companies and research institutions—gives it substantial influence over global AI trajectories regardless of formal governance mechanisms. However, US absence from UNESCO (and thus not party to its AI ethics recommendation) and tensions over UN AI governance processes limit US engagement in some multilateral forums.

Europe

Europe’s AI Act represents the most comprehensive AI regulatory framework globally. Adopted in May 2024 and entering force August 1, 2024, it establishes a risk-based approach with requirements proportionate to AI systems’ risk levels. Prohibited uses include social scoring, exploitation of vulnerabilities, and most real-time biometric identification in public spaces. High-risk systems face stringent requirements. General-purpose AI models have specific obligations. Limited-risk systems primarily require transparency.

Implementation proceeds in phases. Prohibitions became applicable February 2, 2025. GPAI requirements apply August 2, 2025. High-risk system requirements take effect August 2, 2026. Full applicability across all risk categories occurs August 2, 2027. This phased approach allows stakeholders time to achieve compliance while establishing governance architecture.

The European AI Office, operational since August 2025, implements and enforces the Act, particularly for GPAI models. A scientific panel of independent experts advises on systemic risks. Member states designate national competent authorities—market surveillance authorities, notifying authorities, and single points of contact for EU coordination. Denmark became the first EU member state adopting national AI Act implementation legislation in May 2025, providing a model for others.

The AI Act influences global standards through “Brussels Effect”—organizations serving EU markets must comply regardless of location, often leading to adoption of EU standards globally to avoid maintaining multiple compliance regimes. However, concerns exist about regulatory burdens on innovation, particularly for startups and SMEs lacking resources for extensive compliance programs. Regulatory sandboxes aim to support innovation while maintaining safeguards.

United Kingdom